Agroecological Responses for Climate Resilience

- Two Experiences in Costa Rica

Natalia López Espinoza - Independent journalist specialized in Agroecology, collaborator for Cross Cultural Bridges Costa Rica. / Margo Potma - Independent consultant specialized in sustainable food chains, collaborator for Cross Cultural Bridges The Netherlands (1).

Around the world, primary forests along with their species-rich cover are rapidly declining, while expansion of agricultural land proceeds. This phenomenon is one of the main causes of climate change. Knowing that human presence and activity in primary forests cannot and will not be excluded, there is a growing need to find ways to combine agricultural production with nature conservation, while securing the livelihood of families.

Costa Rica is one of the most biodiverse countries on the globe, representing almost 6 percent of the planet's biodiversity. The Costa Rican government and other organizations have been making numerous efforts to protect their natural treasures, but at the same time, various local communities have been facing the situation in different ways. This article investigates two Costa Rican communities that apply an agroforestry logic that includes the cultivation of cocoa. The Yorkin community of the Bribri indigenous people in the Alta Talamanca area and the OSACOOP (2) farmers' cooperative in the Osa Peninsula are implementing different adaptation and mitigation strategies to climate change. While the Bribri find an answer in their cosmogony and cultural background, OSACOOP farmers use approaches more based on their own interpretation of technical advice from support organizations. Interestingly, in both cases the practice of crop diversification is observed as a basis for climate resilience. In this context, this article searches to answer: can agroforestry systems with special attention to cocoa cultivation serve as a solution for humans and nature in the battle against climate change?

ANCESTRAL BRIBRI WISDOM FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE

The cultural practices of the indigenous Bribri are classified as agroecological or agroforestry, but these classifications detract from their culture and identity and their resilient production systems. In the south of Costa Rica, in the Alta Talamanca area, live the descendants of Ditsö Sibö (God) who brought them into the world as seeds to preserve and spread life on earth.

Photo 1: Community of Yorkín, Bribri Indigenous Territory, Talamanca, Costa Rica

The Bribris and Cabécares, together, comprise an approximate number of 13,700 people (3) and have integrated production spaces, very well defined and located at different levels for the protection of ecosystems; especially the soil. Their practices consider biodiversity as the basis of their very existence.

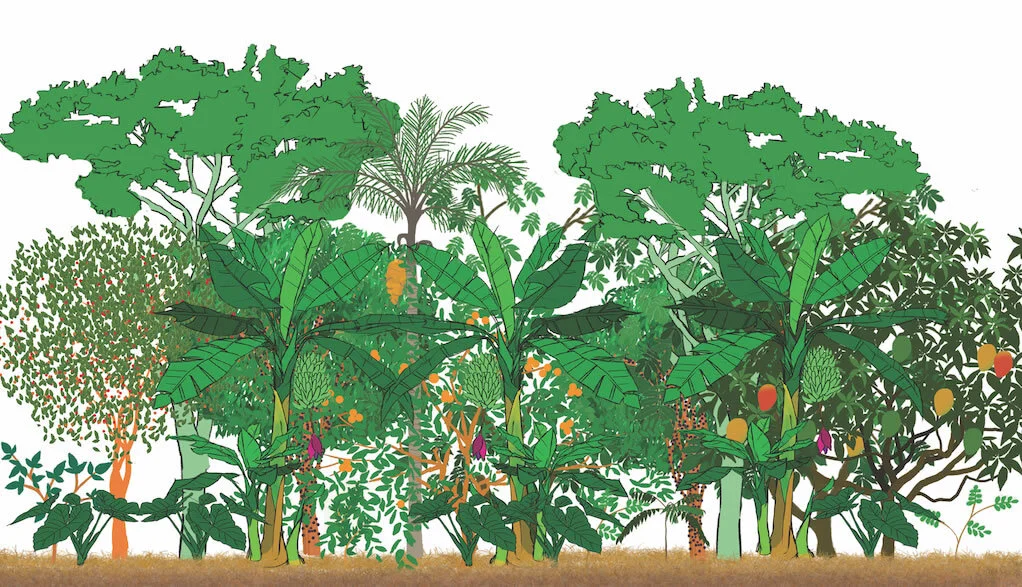

Crops go from the upper canopy to the middle and lower level. The wooded cover on the upper level has timber trees of up to 40 meters that also provide shade; It is followed by the most diverse fruit trees in the middle level and, in the lower level, we find tubers, vegetables, grains, shrubs and medicinal plants. In addition to these strata, their lands are prepared for other uses and management that are scarcely known in common practices.

THE TEITÖ

Teïtö is the space where they rotate beans, corn and rice, as well as wheat and sorghum. Bernarda Morales, a leading producer of the Yorkin community - which is home to just over 200 inhabitants and is settled on the banks of the homonymous river that separates Costa Rica from Panama -, grows yucca (Manihot esculenta), malanga (Xanthonoma Sagittifolium), squash (Cucurbita moschata), ñampi (Colocasia esculenta) and tiquisque (Xanthosoma violaceum) in her teitö:

“Some also grow corn, rice, tomato or chili. What we do is rotate; We do not always sow in the same place. The elders taught us that crops should not be sown repeatedly in the same place and that one crop should not be sown on its own, because diversity enhances the soil and produces cooperative relationships such as beans with corn.”

Photo 2: Producer Saolín Morales in a cocoa plot with interspersed sowing of fruit and timber trees

THE CHAMUGRÖ

Chamugrö is the intercropping of timber and fruit trees, located on the upper and middle levels, which diversifies their income and contributes to the biodiversity of pollinators, fauna and microfauna. "We sow laurel, cedar, cenízaro (Samanea saman), citrus, papaya, banana, cocoa in the chamugrö" tells Morales, who is also the founder of Stibrawpa (4) - an indigenous association that since 1992 promotes the social and economic development of the community, the promotion of indigenous culture and traditions and the preservation of forests and natural beauty. The chamugrö is a biological corridor and host to birds and mammals; it serves as a biological barrier against pests, protects the soil from erosion and makes efficient use of nutrients by recycling organic matter. It also contributes to the capture and fixation of positive CO2 of up to 200 tons per hectare (5).

THE WITÖ

Witö is an area with short-cycle annual crops that are easily accessible: “We raise pigs, laying hens, criollas and free-range chicken, carraco and some others have ducks or gooses. We plant vegetables, tiquisque, mint, and lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus), insulin (Costus pictus), horsetail (Equisetum bogotense Kunth), mastranto (Hyptis suaveolens), turmeric (Curcuma domestica) and cuculmeca (Smilax spp.) ”. The list that Saolin Morales, another producer from the Yorkin community gives us, seems endless: it has more than 60 different crops. The Bribri productive area dedicated to planting short-cycle crops provides food and medicine to families, as well as fodder for their animals.

The way they cultivate so many different species in their plots reflects the holistic conception of the world of the Bribris. The relations of mutualism that occur in their crops also exists between people in the community through "the back hand", a tradition that encourages cooperation and transmission of knowledge through the exchange of workforce between families and communities; an adaptation mechanism that strengthens their culture.

SOCIAL RESILIENCE TO THE IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE

Cultural practices are an agroecological response to climate change, but this merit is not free; it is part of once identity. Bernarda says:

“We have the capacity to adapt to climate change because we have been adapting for years to the problems of the outside world. We have had threats, when the monilia [Moniliophtora roreri] affected cacao and there was no tourism, our men went to the banana plantations to work and many did not return. Our language and culture were lost. Threats will continue, we know, that is why we protect our territory and we seek to encourage young people not to leave and take care of the culture, because if they leave, our culture is lost.”

Photo 3: Bernarda Morales cocoa producer and founder of Stibrawpa, Yorkin

More than thirty years have passed since the plague struck them, but Bernarda recalls to it by demonstrating the resilience of the Bribri community:

“Many of us left and those who returned came back sick from the chemicals in the banana plants. So the women decided to organize themselves and went to sell crafts, but this business was complicated because of the distance. So we decided to bring visitors to Yorkin to share our culture and sell crafts. And so we went out; At first a few visitors came but, with the help of organizations, we improved.”

With an average of 1700 visitors per year, the Stibrawpa association brings dynamism to the Yorkin community. It generates diverse jobs through tourism and articulates the sale of certified organic bananas and cocoa for export markets. These economic activities are aimed at Good Living (Buen Vivir) and maintaining their culture.

ANCESTRAL MANAGEMENT OF COCOA AND CARBON STORAGE

The cultural practices of the Yorkin Bribris in the handling of creating added value to cocoa production, is making their cocoa an especially attractive product for the international markets of the Bean to Bar industry in Europe, where chocolate companies seek quality and traceability of the bean, but also consider clean, social and environmental friendly production.

The ancestral management of cocoa cultivation sequesters up to 200 tons of CO2 per hectare, thanks to the forest cover provided by intercropping with timber and fruit trees. It also protects the soils from erosion and regenerates them with its litter and other shade trees, incorporating organic matter into the soil, maintaining the biota. The Bribri cacao tree is a host for birds and serves as a biological corridor for fauna and microfauna; It also promotes the ancestral Bribri culture. Fruit and timber trees contribute to income diversification and food security and sovereignty. Unlike other indigenous groups producing cocoa, in Yorkin plots are preserved for the cultivation of native cocoa species.

The Bribri conception of development puts the collective value before the individual, which assumes the existence of an interconnection with the elements of nature and protects and integrates them as part of their ancestral family. This same conception leads them to look for answers in the past to move towards the future, thus facing the changes that other cultures wish to impose or those that they themselves wish to incorporate, to maintain their culture (6).

COVID-19

At the moment the pandemic has paralyzed tourist activities, but not in Yorkin, who have set up a centralized garden to supply rice, flour and vegetables to the surrounding populations, food that was brought from outside.

Agroecological resilience is urgent. Ancestral people keep wisdom and knowledge around them and have been giving agro ecological responses in mitigating climate change. But it is necessary to articulate, visualize and recognize this knowledge in order to strengthen it and empower those who hold it.

OSACOOP FARMERS’ SEARCH FOR RESILIENT PRODUCTION SYSTEMS

The Osa Peninsula region on the Pacific coast, in the southernmost part of Costa Rica, is home to 2.5 percent of the world's biodiversity and more than 50 percent of the biodiversity in Costa Rica (7), making it an important biodiversity sanctuary. The region is home to 400 species of birds, 140 species of mammals, 115 species of amphibians (8), 500 species of trees, and 6,000 species of insects (9). Notable species include the jaguar, puma, tapir, howler monkey, sloth, parrot, and pizote. There is an estimated population of 5000 people living in the Osa Peninsula, of which the first group of farmers arrived in the area in the 1950s (before this gold mining activities took place for a few decades).

To protect the natural treasures of the region, Corcovado National Park was established in 1975, bordered by the Golfo Dulce Forest Reserve (RFGD), which functions as a buffer zone around the park (see photo 4). Agricultural activities are still allowed in the RFGD, either under strict conditions. The case of the Osa Peninsula can serve as a micro example of human-nature coexistence, and seeks to find a balance in which both can subsist or even complement each other to adapt to climate change and combat future pandemics.

Photo 4: Aerial of the Osa Peninsula (source: Valter Ziantoni)

LAND USE ACTIVITIES AND STRUGGLES FOR SUBSISTENCE

Apart from the high levels of biodiversity, the Osa Peninsula is also one of the poorest areas in Costa Rica. Local communities in the region are struggling for their subsistence, as their geographic isolation makes agriculture more of a household necessity for smallholder farmers. As the agricultural sector in this region has faced boom-bust cycles of production, it has generally been an unstable source of income. The government introduced agricultural stimulation policies (since the 1950’s) to stimulate the economy in the area. They supported farmers to cut down the forest and grow traditional crops for the market. These policies contributed to continuous changes in crops grown by farmers, trying to respond to fluctuating (international) market prices and demand, but also to agricultural failures due to pests and diseases that destroyed entire crops. Farmers have changed over time from cocoa to corn, beans, rice and cattle to palm oil today.

The cultivation of monocultures is not only threatening the subsistence of farmers through low market prices or pests, it is also depleting the quality of the soil. Therefore, the need for the use of chemicals and pesticides increases, and the risk of deforestation activities increases to obtain fertile land. On top of that, the system is more vulnerable to the effects of climate change (think droughts) and loss of biodiversity. Turning it into a vicious cycle of threats to both humans and nature.

CONSERVATION OF NATURE VERSUS HUMAN SUBSISTENCE

Influenced by the emerging threat of climate change and the loss of biodiversity by agricultural activities, the Costa Rican government unexpectedly changed course in 1990 by introducing Forest Law 7575. The law was to guarantee the conservation, protection and management of forests natural resources, as well as the sustainable use of renewable natural resources in the country. Unlike previous government interference to stimulate agriculture in the area, these policies tie commercial crop production to strict regulations. A positive outcome for nature now began to threaten the farmers' livelihood.

The complex relationship between nature and humans on the Osa Peninsula requires care and alternative means of production. Alexander Solórzano, director of cooperation of the farmers of OSACOOP, explains that

“we are concerned about our environment and we want to protect it, to keep the natural landscape in balance, we need to find climate-friendly production methods, because otherwise we live in a region with a lot of biodiversity but with many poor people. "

CROP DIVERSIFICATION WITH COCOA AS A LAST RESOURCE

In the past five years, farmers began to focus on crop diversification, so-called agroforestry systems, to spread their risks and reduce their impact on the environment. Farmers have started complimenting their palm oil fields with rows of cocoa, plantain and some timber. Palm oil and banana have a double function, they also function as shade trees for cocoa. The first results show that both palm oil and cocoa offer higher yields (both in quality and quantity) when grown together compared to growing individually. This suggests that the quality of the soil has improved and its fertility increased.

This year, farmers are implementing vanilla in the system, which generates a high price on the world market, but also carries greater risks to achieve a good harvest. However, the other two commercial crops of palm oil and cocoa are quite stable and provide resilience to the vanilla. Alexander adds, "The system offers reliability of yield, cocoa can be seen as a subsidy in times when vanilla prices are bad." Farmers no longer have to abandon the production of one crop when market prices are low, they now have other crops to turn to.

Within this system, cocoa fulfills multiple functions, in addition to helping as climate adaptation and diversification of palm oil production, offering a stable alternative source of income for variable vanilla production, and providing farmers with the opportunity to access various markets. But that is not all. Alexander emphasizes the importance of including subsistence crops in the system, a resilient livelihood does not only depend on cash crops for the market. So they also grow rice, beans, tiquisque and corn for animal fodder.

AGROFORESTRY AS A CLIMATE-SMART AGRICULTURE

Agroforestry areas not only provide resilience for subsistence and increase soil fertility, it also functions as a buffer zone around the Forest Reserve and strengthens wildlife corridors increasing biodiversity. The importance of timber in an agroforestry system is not only to improve soil quality and thus crop production, but trees also capture a large amount of carbon stocks. Depending on the design and the crops used in the system, agroforestry can capture between 0.29 to 15.21 Mg CO2 / ha / year in its leaves and 1.23 to 173 Mg CO2 / ha / year in the soil. Trees represent an important part of the response to mitigate climate change and secure farmers' livelihoods. A win-win situation.

Farmers are open and willing to diversify their crops, but they have also become skeptical about the success of land use changes since they have seen the market fail over and over again. Therefore, OSACOOP organized, with the help of a foreign buyer interested in sustainable vanilla from this system and Preta Terra (10), a three-day workshop (see photo 5) to learn more about the environmental, social and economic benefits of diversified production systems. , as well as on best implementation practices.

Photo 5: Excursion to the palm oil plantation as a possible basis for agroforestry design

On the first day, the group of participating farmers formulated a goal, saying:

“with a lot of study and agroforestry knowledge, to overcome climate change and the technical and economic challenges to reach a lucrative and biodiverse production, with a large cooperative of national impact and sustainable for future generations."

This resulted in two different agroforestry designs (see photo 6), based on the crops that farmers want to include in the system. One that can be implemented in current palm oil plantations and another for wastelands.

Photo 6: PRETA TERRA agroforestry design (agroforestry consultancy of Valter Ziantoni and Paula Costa) with cocoa as the basis of the system

The current COVID-19 crisis stresses the importance of subsistence farming and climate adaptation. Farmers should no longer depend solely on external markets for their food. But farmers are also realizing the importance of market diversification for their cash crops, now that international market demand has collapsed. Therefore, the local and national market is being explored to sell processed cocoa and plantain products. Farmers already knew that change was their only way to survive, but the COVID-19 crisis made the need for resilient production systems tangible.

CONCLUSION

The Bribri and Osa Peninsula communities have been applying strategies to adapt to the effects of climate change, while building the resilience of their livelihoods. Both the Bribri community of Yorkin and the farmers of OSACOOP use diversification strategies as a holistic approach to cope with the changing environment. While the Bribri use their cultural codes to increase resilience, having biodiversity as the basis of their existence; OSACOOP farmers began implementing agroforestry systems to continue living in their natural area after experiencing the shortcomings of having a traditional commercial agriculture. Interestingly, cocoa, which is generally regarded globally as a cash crop for the international market, for the Bribri and OSACOOP cocoa is an integral crop of their agroforestry systems that enhances ecosystem resilience and social and economic resilience. In this sense, the adaptive capacity and contribution to mitigating climate change are also being improved. The current COVID-19 crisis further shows the advantages of applying an agroforestry system that increases resistance to current and future pandemics, providing food security and limiting risks. In the long term, this will become increasingly essential when coping with more extreme weather conditions.

Both examples show us that we need a different perception of the economy, one that is holistic and also value-based, to be climate resilient. A system that not only focuses on economic growth, but also includes values such as health, community, solidarity and harmony with nature. To establish this, we need effective collaboration between all levels to create effective arrangements for managing local resources and food production.

Published in: LEISA, Revista de Agroecologia, 'Cambio climático y coyuntura 2020, reflexiones y respuestas', Volumen 36 (2), Julio 2020

REFERENCES

CCB supports, co-designs, facilitates and implements short and long-term initiatives aimed at intercultural learning (with an emphasis on South to North). They have extensive knowledge regarding sustainable food chains and create and / or enhance transitions that contribute to "Good Living"

Cooperative for the Marketing of Oil Palm Producers of the Osa R.L Peninsula

It must be said that in Costa Rica there are 8 ethnic groups distributed by law in 22 indigenous territories, which reach a total population of 104, 143 people, which represents 2.42% of the country's population.

Indigenous association founded in 1992 that promotes the social and economic development of the community, the promotion of indigenous culture and traditions, and the preservation of forests and natural beauty.

http://infocafes.com/portal/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/345.pdf

https://www.revistas.una.ac.cr/index.php/praxis/article/download/4382/4212/

Toft, R., and Larsen, T. H. (2009). Osa, where the Rainforest Meets the Sea. Costa Rica, Zona Tropical Publications.